Describing the Journey

A series of reflections from the perspective of the participants. They have been developed, in part, by drawing on the insights from the journals that the cohort kept during the process.

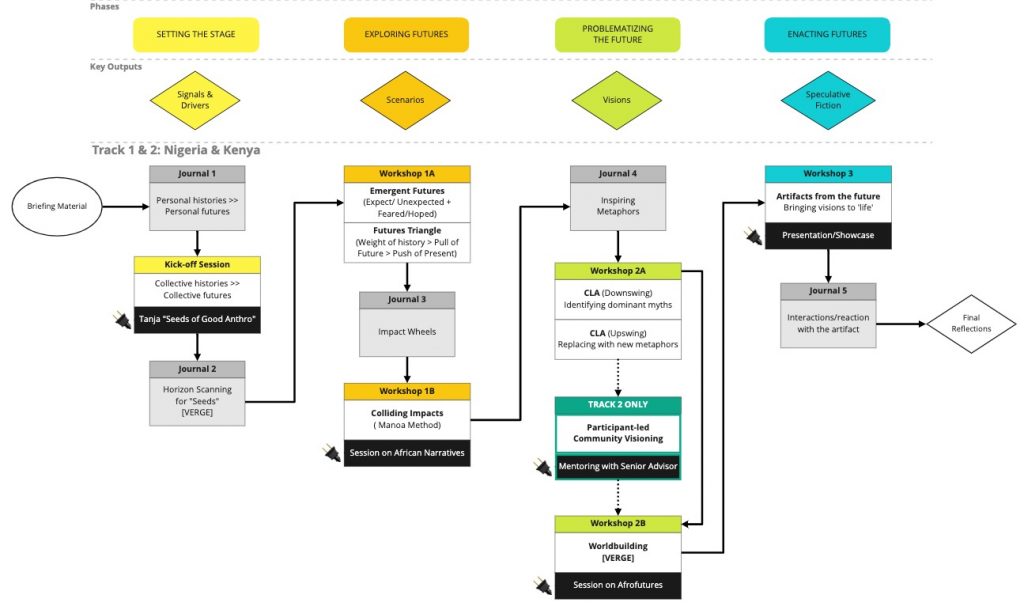

The design of the whole process was led by Pupul Bisht and Johann Schutte from the School of International Futures with input from the cohort and the African facilitators and hosts.

- Setting the Stage: Journal 1

- Setting the Stage: Kick-Off Session

- Setting the Stage: Journal 2

- Exploring Futures: Workshop 1A

- Exploring Futures: Journal 3 and Workshop 1B

- Problematizing the Future: Workshop 2A, Journal 4, and Workshop 2B

- Problematizing the Future: Community Visioning

- Enacting Futures: Workshop 3 and Journal 5

Setting the Stage: Journal 1

Elise Boulding, commonly referred to as the “matriarch of peace studies”, developed the concept of “The 200 Year Present”. The purpose of this notion was to help people grasp the connectivity between the past, present and future. Boulding suggested that at any one time during an individual’s life, they will share that moment with someone who was born 100 years ago, and someone who will be alive 100 years to come. Therefore, people who come across this concept appreciate the effect on the present of events that occurred 100 years in the past; similarly, present-day events have an impact on lives 100 years to come.

“The 200 Year Present” concept was used to welcome participants into the African data governance futures process. Since most of the participants were novices in the realm of futures and foresight, this concept was an effective way of easing them into the program. The first Journal activity required participants to familiarize themselves with Boulding’s concept by providing insight into the past and future of their lives, and in extension, that of their communities. The past and future were examined on three fronts; one year, one decade, and one century. Participants detailed how their personal and their communities’ lives were different one year, one decade, and one century prior to the exercise. The examination of the past was more of a recollection of events and contexts that were dissimilar in years past. Contrariwise, their examination of the future required them to be imaginative and conceptualize the ways in which they felt their lives would be different a year, a decade, and a century from then.

The first journal activity marked a shift in the way participants understood the nature of time and progress, with regards to foresight. The future is an intimate part of the present moment, because it is the activities undertaken now that shape the future to come, be it in one year or 100 years. If World War 1 had taken a different turn of events, there are numerous aspects about modern-day life that would be different, from the existence of certain nation-states to development of particular inventions and thought models. Comprehension of this concept and its implications set the stage for the Kick-Off Session.

Setting the Stage: Kick-Off Session

“The 200 Year Present” enabled participants in all 3 cohorts to identify certain themes that they noted about both the past and the future. In the Kick-Off Sessions, participants initially had to familiarize themselves with each other, noting that none of them had interacted prior to the Data Governance program. Zoom Breakout Rooms were used for this purpose, where pairs of participants were placed in breakout rooms and encouraged to find out more about each other from the other’s occupation, to their area of residence, and other pertinent issues relating to their identity and values. As strangers, an icebreaker was necessary to lighten the setting and enhance interaction between the participants. An example is the icebreaker model that was used in the Kenyan Cohort where the participants, within the breakout rooms, were required to state imagine that they are on a journey, and to describe the means of travel as well as the intended destination. However, their partner within the breakout room was required to present their personal profile, as well as their described journey to the rest of the cohort in the main session. This process not only increased familiarity between individual members, it further shed light on the aspirations, ideations, and dreams of the various participants. While some were on a journey to Utopia on sprained ankles, some were in search of large water bodies while other were using Hyperloop to travel to foreign continents.

The increase in familiarity was enhanced by the next set of breakout rooms where the cohorts were divided into two groups, and discussion related to the identified themes of the past and future were discussed. Despite this being the introductory event in the program, and the first time that participants were meeting each other, commonality in the themes they had identified swiftly emerged. Within their groups, participants discussed their collective histories and futures by identifying themes that related to either of these time periods. Examples of important themes from the past that were identified include limited access to information and the aspect of locality as opposed to the contemporary globality. Some themes from the future identified included climate change and e-everything, to represent the increasing digitalization of every facet of life.

The first journal activity and initial workgroup discussions paved the way for Tanja Hichert to introduce the cohorts to the “Seeds of the Good Anthropocene.” As much as the program was designed to be a group foresight activity, it was equally a learning activity since a bulk of the participants were new to the various terms, concepts and tools introduced. The plug-in session with Ms. Hichert commenced with an explanation of the term Anthropocene, which participants learnt refers to a new geological epoch where human activity is a dominant force shaping ecosystems at a global scale. Basically, the Anthropocene refers to the current geological period that began when humans started affecting and shaping ecosystems the world over. Thus far though, the Anthropocene has been inundated with a development paradigm marked by exploitation of nature, continuous production and consumption, and privatization of common resources. This paradigm has brought about a convergence of crises in the modern age that necessitate a shift in the way that humans develop and progress.

One of the most powerful tools that emerged from the Data Governance process concerns story-telling. Participants initially learnt about the power of stories to shape the future in the first plug-in session with Ms. Hichert. Stories define the reality we live in, but they also have a gargantuan role in creating the same reality. Individuals, societies, or the world at large are more likely to confront a scenario of doom and gloom if the dominant stories have themes of disaster, fragmentation, and breakdown. Positive stories, on the other hand, have the power to drive much more hopeful transformation; hence the importance of the “Seeds of the Good Anthropocene”. These seeds can be stories, or small-scale, experimental projects and initiatives which employ new ways of thinking or doing. They can alos take the form of new social institutions, technologies, or frameworks of understanding the world. Such seeds typically exist at the margin of current worldviews, and often come from non-dominant groups/cultures.

Setting the Stage: Journal 2

The second journal was the final activity in the primary phase of “Setting the Stage”. Armed with information on the interconnectivity between the past, present and future, and about the “Seeds of the Good Anthropocene”, participants were now ready to identify such ‘seeds” within their immediate communities, societies, and polities. For the second journal activity, participants were to examine their local and communities for small and big signals of change, as well as other emerging issues and phenomena they believed would impact the future. Participants were implored to not only identify the most visible and prominent signals and phenomena, but to further uncover new and unanticipated signals of change. These are the signals and issues that the status quo ordinarily overlooks when planning for the future of African countries and jurisdictions.

To ensure that the participants identified signals and issues that were encompassing and cut across the various dimensions of human life, the VERGE framework was adopted for this activity. The VERGE tool enabled the cohorts to frame and explore the various issues through the lens of six domains:

- Define: The concepts, ideas and paradigms people use to define themselves and the world around them e.g., religion, social values, scientific models, public policy etc.

- Relate: The social structures and relationships that organize people and create organizations e.g., demographics, family and lifestyle groups, government, education etc.

- Connect: The technologies and practices used to connect people, places, and things e.g., information technology, language, media, the arts etc.

- Create: The technology and processes via which humans produce goods and services e.g., engineering, innovation processes, materials science, wealth, nanotechnology etc.

- Consume: The ways in which humans acquire and use the goods and services they create e.g., consumer goods, healthcare, food and agriculture, house and home, natural resources etc.

- Destroy: The ways in which humans destroy value and the reasons for doing so e.g., waste, violence and killing, attempts to undermine rules and norms etc.

The second journal activity marked an increase in the level of detail required of participants. In the first journal activity and the initial workshop, the participants thought in broad strokes. They recollected their collective histories, and imagined what a collective future could look like. Their ideas and discussions were not limited to their local, or even African context. By the end of the first phase however, the second journal activity demanded that they broaden their thinking such that they considered all facets of society and life. The cohorts encountered a juxtaposition of concepts through utilization of VERGE where they both had to narrow and broaden their perspectives. Rather than think in general global terms as was the case in the first journal and workshop, participants had to narrow their focus to identify seeds of change in their local communities, countries, and continent. This narrowing of focus involved a broadening of horizons where participants had to identify seeds through each of the six domains included in the VERGE framework.

Exploring Futures: Workshop 1A

With the stage now fully set, participants were not ready to explore the various futures that might result from the various seeds, signals and drivers identified. One factor that participants were increasingly becoming familiar with by this stage was that the various elements identified were not necessarily positive, and that they occurred all along the positive-negative continuum. Therefore, there are various signals and drivers that the participants had identified in the previous phase that they might find unpalatable. However, that is their primary function; to simply act as indicators and to enable the participants to conceptualize as many scenarios as possible from the identified factors. In the first workshop of the second week, participants discussed the various expected and unexpected signals and drivers they identified through the VERGE framework, and how these related to futures that they either feared or hoped for.

For this workshop, participants were introduced to another future tool: The Futures Triangle. This triangle demonstrates that a plausible future is the result of three factors: the weight of the past, the push of the present, and the pull of the future. Through this tool, participants were able to connect their two journal activities, and use the information gathered to determine the most plausible futures. The cohorts had identified factors that contributed to the weight of the past and the pull of the future through a study of their “200-year present”. In the second journal activity, the cohorts had recognized various present signals, drivers and phenomena that comprised the push of the present. The Futures Triangle tool helped participants connect the information gained from the different activities, and understand how vital all of it was when developing plausible future scenarios.

Exploring Futures: Journal 3 and Workshop 1B

‘Make like a tree and leave’. “Time flies like an arrow; fruit flies like a banana’. How does the human mind make the necessary mental connections that enable formulation and comprehension of puns such as these? And how does that tie in with the futures process?

Bisociation, coined by Arthur Koestler, refers to the simultaneous mental association of an idea or object with two fields ordinarily not considered as related. Koestler used the term to illustrate the combinatorial nature of creativity, and demonstrated how the pun is one of the best examples of bisociation. A pun is a bisociation of single phonetic form with two meanings – two strings of thought tied together by an acoustic knot. Bisociation was a vital element in the cohorts’ third journal activity. This journal activity marked a pivot point for the participants regarding the increased level of specificity and detail required. While participants were free to think in broad and general terms for the first journal activity, they had to both narrow the contextual scope and widen the dimensional lens for the second journal. For this activity, participants had to be even more imaginative and comprehensive to accomplish the task required. The primary tool used in the journal activity were Impact Wheels, hinged on the Manoa Method.

The participants were required to take a particular change identified, for example “shift to remote working”, and imagine it as a resultant mature condition 30 years out. In this case, the resultant condition could be “most professionals now work from home.” Participants were then to place the resultant condition in the center of the impact wheels, after which they were to identify the primary and secondary impacts of the conditions. To guide the participants on how to identify the various impacts, the STEEPV categories were used. STEEPV refers to Social, Technology, Economy, Ecology, Political, and Values. Therefore, each of the participants had to identify a primary impact of their mature condition in each of these categories, and further identify up to three secondary impacts stemming from the primary impacts.

During the second workshop of the week, the cohorts learnt that the process they had undertaken in their previous journal activity was part of the Manoa Method. The Manoa Method is credited to Dr. Wendy Schultz, and it seeks to maximize the degree of difference from the present so as to obliterate blind spots created by stale assumptions, and potentially identify “black swans.” Dr. Schultz notes that the method is directly attributable to Jim Dator’s Second Law of Futures Thinking – “the only useful idea about the future should appear to be ridiculous.” In this regard, the impact wheels activity in the journal activity was meant to stretch the imagination of participants to the extent where they populate their wheels with impacts that they themselves might consider as far-fetched or improbable. The best method of carrying out the activity was to have participants free to challenge their dominant assumptions on the persistence of current conditions, inflate the possible impacts to a point of absurdity, and reverse strengths or constraints that exist in the present. These principles are crucial to effective utilization of the impact wheels and the Manoa Method, and are loosely based on Edward de Bono’s main creativity processes.

The utility of bisociation in the use of the impact wheels and the Manoa Method is revealed in the relationships of the primary changes. Since each impact wheel centered on an emerging change stated as a mature condition, participants needed to identify changes that were in different dimensions, or STEEPV categories. By identifying changes and mature conditions which demonstrate considerable statistical independence, participants are able to use bisociation to develop more creative and surprising results. Therefore, use of changes that all stem from a single dimension, for example technology, would mean less orthogonal changes, and thus lesser creative impacts. An example of highly orthogonal changes would be such as climate change, blockchain, and decentralized governments, which represent the ecological, technological and political STEEPV categories.

In the workshop, the cohorts learnt that the Manoa Method’s utility lies not in the individual’s awareness of change, but rather the primary and long-range impacts of change, and the possible results of the collisions of these impacts. The gestalt of the identified changes and impacts will determine the emerging scenarios of alternative futures. In order to build the scenarios, participants worked in pairs to identify individual secondary impacts from their impact wheels. For each pair, there were a total of six impact wheels, which were then placed in two sets where one set comprised of two wheels from one participant in the pair, and one wheel from the other participant. Participants then had to identity a single secondary impact from each wheel in the set, and use these to develop a scenario that describes that fits the chosen impacts. Each pair developed two scenarios, with each scenario given a title akin to a bumper sticker phrase that captures the essence of the scenario. Similarly, the pairs were encouraged to imagine their scenario as a film or documentary, and in turn, give it an apt title. The process birthed scenario titles such as “If you put lipstick on colonization, it’s still colonization”, “1984 Today”, “The World in Your Hands”, and “Is Social Welfare really for all?”

The third session marked a significant defining moment for the cohorts. Firstly, the various participants grew increasingly familiar with the various futures tools that they had been presented with. Most of the participants were unfamiliar with the range of tools and techniques used in foresight research, meaning that there was a learning curve in the use and application of these tools. By the third session, however, participants could name and identify the various tools used, and understand their functionality and expected outcomes. Second, the third journal activity and the extended use of the Manoa Method in Workshop 1B exemplified just how unpredictable the future is. By being forced to pinpoint numerous secondary impacts in the various STEEPV categories, the cohorts had a growing sense of the range of impacts that can stem from a single event. Furthermore, the mix and match aspect used in developing the scenarios showed how disparate factors can interact to shape a distinct future.

Lastly, the cohorts confirmed the importance of stories to the futures process through the plugin session with Dr. Mshai Mwangola and Aghan-Odero, members of The Orature Collective. The session reminded participants of the significance of the story-ing process. Can people create something they have not envisioned? Hardly – hence why conditions for hatching the future have to be created. The conversation on stories left all the cohorts with a feeling that they have a largely severed connection to their cultural stories, languages, myths, metaphors, and resources. Most participants observed the disconnect that modern-day Africans have with their cultural roots, and the role played by oppressive systems such colonialism, and even mainstream educational curricula. A significant part of the cohorts’ African and cultural stories has been lost, stolen, or devalued, to the extent that they find themselves desiring sources that can repair and re-establish this lost connection. Dr. Mshai used the movie Black Panther to demonstrate the narration of ‘African’ stories, and the way in which art facilitates deep examination of our current condition. She defined art as “a creative facilitated community conversation within a particular social context.” In the case of Black Panther, it was a creative endeavor facilitated by the writer, director, producer and team involved in bringing the film to life. The audience is the community, and the conversation involves the multiple perspectives used to perceive the film. In the Kenyan cohort for example, it was noted that while the film’s creators might have envisioned T’Challa, King of Wakanda, as the protagonist, some people might regard the ‘villain’ Killmonger, as the protagonist. Dr. Mshai suggested that maybe the women in the film were the protagonists, noting how their role shaped the film’s storyline.

Problematizing the Future: Workshop 2A, Journal 4, and Workshop 2B

The third phase in the process took participants from the horizontal process that marks the bulk of foresight work, to the vertical process of examining the different layers that define current issues. In Workshop 2A, the cohorts were introduced to the Causal Layered Analysis (CLA), a paradigmatic tool which reveals deep worldview commitments hidden beneath surface phenomena. The utility of the CLA lies not in predicting the future, but in creating transformative spaces for the creation of alternative futures. By using the CLA, the cohorts were able to understand that issues are similar to an iceberg, where the visible part is only a miniscule part of the underlying and causative factors. The participants understood the CLA as a four-level analysis that explores the litany, systems, worldviews, and myths and metaphors linked to an issue. While the litany represents the visible part of the issue, and describes how people feel about the issue, the invisible part comprises the systems that create the situation, the worldviews that shape it, and at the very bottom, the myths which represent the underlying stories that feed the situation. Through use of the CLA, participants were able to understand that exploration of issues requires a deeper analysis than that provided by common empiricist orientations that merely “skim the surface.”

Using the iceberg symbolism, participants understood that the largest factors, and those that needed addressing occur under the visible surface. The most significant of these factors are the myths and metaphors that occur at the bottom of the iceberg, and actually make up the largest portion of the iceberg. Therefore, the role that myths and metaphors play in the development and occurrence of surface level issues and situations is a gargantuan one, and one that can only be addressed by uncovering these myths and metaphors. Use of the CLA therefore enforced the part that stories have to play in the variety of issues and context that humans face in their daily lives. Participants were therefore encouraged to use the CLA tool in reverse by creating new metaphors that were unique to their cultures and countries, and use these to develop new worldviews, systems, and surface level litany. This task was partly accomplished through Journal 4 where the participants developed their new metaphors, and Workshop 2B, where they applied these metaphors in the creation of new worldviews, systems and litany.

This workshop additionally featured a plugin session with Charles Onyango-Obbo, who covered material related to Afrofutures. He covered several themes relating to the possible direction that African countries and the continent as a whole might take. Some of the specific content he detailed concerned the rise in private security, fueled both by the growing inequality gap and the increasing development of technological cities. On the latter point, one aspect that he observed concerned the possible secession of the rich from the poor, through the development of cities and real estate development particularly targeted at the rich. He also noted the large role that availability of water will play in determining which cities people will flock to in years and decades to come, for example, Nairobi might witness a decline in population due to the increasingly dire water situation there. People will prefer residing in cities with access to water, such as those around Lake Victoria.

Problematizing the Future: Community Visioning

The community visioning aspect of the program enabled participants to interact with their communities and gain insight into what different people within the community thought about the future of data governance, amongst other issues. Community visioning as a foresight tool stems from the work done by Elise Boulding and Warren Ziegler. These futures practitioners intended for the envisioning process to be one highly reliant on “the spirit”, whereby practitioners needed to be fully engaged in the process if a vision is to be enacted. In this regard, community visioning has little to do with forecasting, futures, social engineering or cognitive mapping. Instead, the envisioning process entails dialogue, deep imaging, deep listening, and deep questioning. Community visioning is more about yielding rather than forcing; practitioners should be aware that there is no “idle chitchat.”

Viewed in this way, the different methodologies and outcomes of the community visioning projects carried out by different participants in their different countries and regions makes sense. Each of the participants sought to engage their communities and understand what they thought about certain issues. The one common factor throughout all the visioning exercise weas that the opinions and information gained from the community participants were key, and the role of the individual practitioner weas simply to facilitate, listen and guide. Additionally, the manner in which the community visioning was carried out was also affected by the COVID19 pandemic, as most of the countries were under some form of restrictive measures including curfews, lockdowns, amongst others. Therefore, while a typical community visioning exercise would have people meet ion the same venue and carry out visioning exercises individually and within groups, the participants had to find alternative ways to sourcing information from different community members and stakeholders.

Enacting Futures: Workshop 3 and Journal 5

The final phase of the program placed participants in the driver’s seat. Having developed various metaphors and scenarios, they now had the opportunity to develop artefacts they believed would contribute to a better future, and additionally create their visions of the future in a narrative form. Participants were able to utilize the information they had gained on the role, importance and use of stories to create narratives of the futures they desired. This phase demonstrated the evolution that the participants had experienced in the way they perceived the future. At the beginning of the process, most of the expectations and visions of the future leaned towards techno-deterministic and techno-utopian outlooks. However, by the final phase, participants were aware of the unpredictability of the future, as well as the possibility that positive and negative elements in the future can co-exist. In this manner. Therefore, the vision stories that the participants developed, despite being generally optimistic and utopian in their depiction of the African future, also recognized some bleak aspects largely associated with the nefarious intent of certain humans, but also the adverse effects of certain technological advancement.

This aspect was similarly noted in the artefacts of the future that the participants developed within their groups. Some of the artefacts created include an idea bank, gender-inclusive processor, an election pager, and virtual museum. Although these artefacts were generally imagined as highly useful technological tools that would address various problems currently faced on the continent, participants also highlighted various ways in which these technologies could be abused. These artefacts and visions developed demonstrated that although largely utopian futures are desired, such futures can equally feature dystopian undertones. This final phase therefore marked a large pivot point in the way that participants understood the futures process. One may want and desire a largely utopian future marked by sustainable technologies that work for the people, and do not “work the people.” However, the participants understood that they have to be aware of all the seeds of change that could contribute to both desired and undesired futures. Furthermore, they realized that as much as technology may change, evolve, and make work more efficient, humans will still be humans. Therefore, even though technology may play a role in tempering widespread effects of human vices such as greed and corruption, it will hardly stem out such aspects of human nature.

The final journal activity required all participants to converse with their family, friends, acquaintances and other people within their online and offline communities. The participants had an opportunity to showcase their artefacts and record the reactions and comments from the people who interacted with the artefacts. This exercise helped the participants emerge from the “ivory tower” bubble within which they were immersed during the program, and actually seek opinions as to what people thought about the futuristic artefacts developed. The participants were further handed the reins of the process in the final journal when they were required to provide specific input on the main issues they regarded as vital concerning data governance. The participants were encouraged to imagine themselves as president of their respective countries, and in this regard, they were to provide specific steps and measures they would take around securing a healthy data governance future for their respective countries and the African continent as a whole.